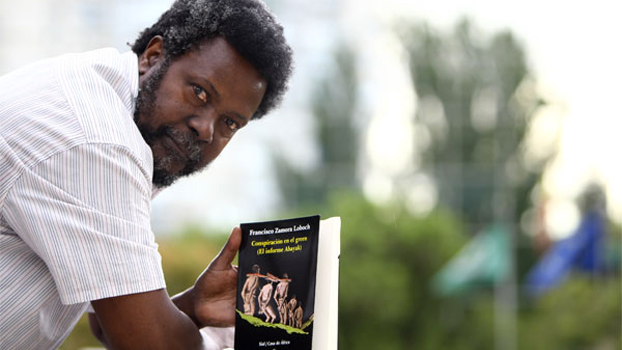

Francisco Zamora Loboch[1], or simply “Paco” to those who know him, is one of Equatorial Guinea’s best-known writers. Born in 1948 on the Equatorial Guinean island of Annobon, his life has been profoundly marked by his country’s passage from Spanish colonial rule, to independence, to dictatorship, to diaspora. Although he came to Spain to study at university in 1968, the ascent of Francisco Macías Nguema’s brutal regime forced thousands of his compatriots into exile, thus making Zamora’s Spanish sojourn permanent. In 1979, Macías’ equally ruthless nephew, Teodoro Obiang, assumed the presidency, further cementing the impossibility of Zamora’s return. Zamora has since established himself as a journalist in Madrid. He has worked for several publications over the decades, most notably as a sports editor for As. His literary works, which include essays (How to be black and not die in Aravaca, 1994), poetry (Memory of Labyrinths, 1999; From the Viyil and Other Chronicles, 2008); and novels (Conspiracy on the Green, 2009; The Caiman of Kaduna, 2012), examine such pressing issues as the role of nationalism in a land marked by ethnic tension, poverty, and state terror; the experience of exile in a former colonial metropolis; the contested belonging of an African nation in the global Spanish-speaking community; and the role of humor in bringing about change.

On May 28, 2013, Paco sat down with me in his Madrid office to talk about his life and his literature.

*****

Martin Repinecz: Can you talk a bit about how you came to Spain and about how you became a writer?

Francisco Zamora Loboch: Well, I was already a writer as a child. I have a poem that describes it. In Annobon, there were not many people that knew how to read in that period. When the mail boat came, the older men and women always depended on the kids, on the young people, who knew how to write, to write the letters. So from then on, I began to write, which was good because it was very well paid. What I mean is that, the better your letters were, the more yams you had, the more plantains you had, you even had more fish, etcetera. So I began writing then, or rather, I began to know the importance of what writing is.

And in terms of coming to this country, when I was young like you, it seemed I was as smart and intelligent as you–people believed that I was smart and intelligent, like you!

FZL: And they gave me a scholarship, so I came here to study economics. But after a while I realized that what really attracted me was journalism. So I switched to journalism.

MR: And that was in the ‘60s, right?

FZL: More like the ‘70s. I’m not that old; don’t be a jerk.

MR: And when did you begin to write creatively?

FZL: Even in Guinea I began to write poetry, perhaps when I was about 17 or 18. And even before, because as a kid, I learned to read very early; I think that I could read even at three or four years old.

MR: Your father was also a poet?

FZL: My father was a poet and schoolteacher. So, for me, to discover reading tebeos, or comics, as they are now called, was a very gratifying world. But it was also problematic because now my older sisters remind me how much I would laugh at them because they didn’t know how to read. At six or seven, I would still tell them, “how is it possible?”, and such. So obviously I began to get into problems, but of laughter; I have always laughed a lot at the ignorant.

FZL: But because the ignorant are always stronger, they always end up bringing you down by hitting you, or beating you up, or something like that. So anyway, yes, I began to write in Guinea, and when I arrived here, I underwent, naturally, a transformation of everything I had written, which was about palm trees, and similar things. And upon arriving here, thank God, I found people who were very critical with respect to politics and history, etcetera, in the classrooms of the school of journalism. I was very lucky in that sense because for others to be critical and tell you, “What is all this stuff about palm trees and coconut trees?” and such, forces you to get with the times. And as you write in newspapers at the same time, you begin to realize that regionalism has no raison d’être if it doesn’t have its projection in a common tree of culture. One cannot simply spend one’s life talking about ancestors, about caves, about palm trees and coconut trees; no, no, no. One must integrate all these things, as a certain Brazilian musician would say, in a common culture.

MR: And when you were small in Annobon, what texts were available for you? You mentioned comics, right?

FZL: Comics! Captain Thunder, Jabato, Mortadelo y Filemón; whatever there was from that period. I didn’t read any interesting books, if that’s what you’re asking.

FZL: Was I already reading Dickens? No. Not at all; my culture was limited to comics; to the world of Captain Thunder, the world of Jabato, the world of Mortadelo y Filemón; of the Guerrero del Antifaz; just like any Spanish child.

MR: And Western novels as well, right?

FZL: Ah yes, of course; my father had very good Western novels, but he didn’t let me read them. But I looked for them and found them. An in addition, it so happens that a beautiful story has come out in recent years about Western authors. I don’t know if you have read about how the authors that were persecuted by the Franco regime took refuge by writing Westerns, mysteries, and crime novels to survive, and they would use pseudonyms like Clark Karrados, like Silver Kane. The only one that used his own name was Marical Lafuente Estefanía. I am very taken by that moment. As an enthusiast, not to show off my readings. Now, when I began studying at the Middle School in Santa Isabel, or Malabo, or Clarence, since it has three names…[2]

MR: Pardon, you left Annobon at a certain point?

FZL: Yes, of course; my father was a teacher, and when they sent him to Santa Isabel, I went there too. So two or three years later, I began studying at the Middle School Institute. When I was at the Middle School Institute, they started to allow black children to enter, because before the Institute was only for white children. So starting in the year ’58, when Equatorial Guinea was declared a province of Spain, just like Albacete, then we [black children] could also attend the Institutes. That is when I found myself with competent teachers who taught me who Juan Ramón Jiménez was, who Cervantes was, who other writers were, etcetera. And that is when I came in to contact with great literature, and when I began to read seriously, especially Juan Ramón, whom I read a great deal; Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer; in short, anything that people read in that period. And I remember perfectly when I read Platero y yo, that I was impressed at how one could write so well. And of course Juan Ramón Jiménez’s poems, even if he didn’t influence me much later on, but this fills you with culture, don’t you think?

MR: Yes, definitely. Even when you wrote letters in Annobon, you wrote in Spanish?

FZL: In Spanish, in Spanish. If not, what purpose did it have? From Annobon, you can only go to Santa Isabel, or Fernando Pó, or Bioko, or Malabo.[3] That was the vital itinerary of an Annobonese person. An Annobonese person would go to work in Malabo to build his house, etc. So we had no other panorama, and we are still that way today. In other words, an Annobonese person’s ideal is to set foot in the land of the Bubis,[4] to accumulate money or material to build a house of stone or a house of cement, etc.

MR: Can you speak a bit more about identity in Annobon? How do people on that island feel their Annobonese identity with respect their Equatorial Guinean identity?

FZL: The Annobonese feel very, very very Annobonese. I think that we feel Guinean because of the Bubis. Because the relationship between Annobon and the island of Bioko, or the island of Fernando Pó, however it is called, has always existed. Because as I have told you, it was our link to know what was happening in the world, to be able to buy things, to be able to use something called money, to have relationships with white culture. So of course, from Bioko, being connected with the mainland is no problem. At the end of the day, you are in Africa. Whatever you do. This is something that Africans don’t know: at the end of the day, it is going to be Africa.

MR: But the Annobonese identify more with the Bubis than with the Fang?[5]

FZL: Yes, of course. The contact between Annobon and the Fang is of the last forty or fifty years. By contrast, the contact between the Annobonese and the Bubis is many centuries old. We didn’t go to the continent, we went to the island in search of opportunities. That is where the Bubis are. But it is a melting pot, the capital, which is formbed by Bubis, Spaniards, and others. What it means to be a capital. A small one, but still a capital at the end of the day.

MR: And how was the experience of living in Santa Isabel [present-day Malabo] for you?

FZL: Of course! There I met my life-long friends, those who would become my friends, who were all a bunch of ruffians. My father was also in charge of a reform school for young people. So imagine, a kid my age, surrounded by so many scoundrels, delinquents, crooks! My whole life I’ve been around crooks, rascals, thieves, freeloaders! These were my friends!

FZL: And in addition to those I met in the Institute, I also met many friends in a semi-fascist experience, which was the OJE, the Spanish Youth Organization, when I came to Spain in ’62-’63. But that OJE was a work of Franco, and people used to say Franco called it his pet project, or something like that. Its purpose was so that Guinean teenagers, at age 14, 15, or 16, could come to the peninsula, to Spain, to integrate with other Spanish kids. So of course, your universe changed in two or three trips! It was amazing, because from the racial discrimination of Guinea, from the supremacy of whites over blacks, you come here and you think to yourself, “What the hell is this? I am just the same as these guys!” They would pull your leg, and you would pull theirs, and you would be integrated in a day or two. So the OJE played a very great role despite being a fascist organization of the youth of Equatorial Guinea of that period because it allowed them to leave the colonial environment and enjoy Spain. But certainly, the enrichment of this semi-fascist, para-fascist experience—can you imagine, with the blue and khaki uniform?—enabled us to wake up from a sluggish, colonial world. And it was a whole generation: it was not just me, but hundreds of kids that would come here in the summer to the OJE’s camps. Although Macías[6] finished off all these people, some saved themselves.

MR: So, when you came to Spain to start university, did you plan on going back to Guinea?

FZL: Yes, of course; I had no interest in staying; all the romanticism that I might have had for this country had been exhausted by the time I was 18. At 18, I knew it all.

MR: And with the OJE, you would come to Madrid?

FZL: Ah, no; they were incredible experiences for a kid born in Guinea. At 15, they left you in Cádiz in a boat. They would give you just enough money and a map, and they would tell you where you had to go and what day you had to be there. So we had to figure it out, either walking, or hitchhiking, or however we could to get to these places, of course. Imagine the experience you would get in the ‘60s around here. I remember one time we went to Galicia because the camp was in a place called Sada, a very famous beach. Six of us little Guineans arrived here with our satchels and whatnot, and the leader said, “OK, today we are going to make a paella.” We had the rice, we asked for a paella pan, and we started making the rice, and a couple of ladies approached us. “What are you doing?”, they said. “We are going to make a paella.” “Where are you from?” “From Guinea.” “Since when do you make paellas?” We told them, “No, it’s just that…”, and they said, “Look, sons: you are very young; you look great, very handsome. Go for a swim. Enjoy Galicia in peace. And when you come back, don’t worry, because we will make you a paella.” Wooooow! And when we came back, that was a huge paella, a party!

MR: So you said you came to study economics but then you switched to journalism, right?

FZL: Yes, in the Complutense.

MR: And you were at university when Guinea became independent?

FZL: No, I was there [in Guinea], in the Plaza de España, although I don’t know what it’s called now.[7] I was there that day.[8]

MR: Oh, you remember the day! What happened exactly?

FZL: Well, after that, about two months later or so, I came to Spain. And later came everything with Macías: the murders, the brutality, and so on, but I was here while that was going on. Later, we organized a few plans to return, but they failed; all of our attempts failed. We were also very naïve; we didn’t think money was important.

MR: So, in the early years, you were involved in political movements?

FZL: Yes, I always have been.

MR: Let’s talk for a minute about your career as a journalist. Can you speak a bit more about how you came to be a sports journalist in particular?

FZL: Ah, yes, because on one occasion I was talking with one of my teachers, and I was obsessed with Guinea. So he told me not to be so obsessed with it, and that I dedicate myself to journalism. First I had to subsist, and second, I shouldn’t label myself too strongly. So, I have always been alternating one thing with the other. But above all, in my opinion, where I have written the best has been in the world of sports because as a young man I was a great athlete. That is definitely true. I did track, basketball, hurdles, and of course soccer.

MR: Your last novel, El caimán de Kaduna, is about soccer. I assume your experience reporting about soccer helped you to write it?

FZL: Yes. The newspaper As has sent me to practically all the soccer championships in Africa. In the World Cup in Germany,[9] four or five African teams classified, so I had to go to all those African countries to report how the World Cup was seen there. I was at the African Cup of Nations in Ghana.[10] And at the one in Egypt.[11] And at the one in Angola.[12] And then I was in South Africa recently for the World Cup.[13]

MR: And when you were in all those countries, did you manage to establish contact with other African writers?

FZL: No, I was working like a madman. Because you have to fill two pages of newspaper every day. You don’t have time for anything. There is no time for anything except to eat badly. But it is the best time to visit those countries. You see the national explosion, the national depression, you see people who have nothing to do with soccer criticizing soccer. In addition, the organization isn’t usually very sophisticated. Here, if you show your press pass, they send you to a different place, and from there you have to go somewhere else. But not there. I prefer that chaos. It is more entertaining.

MR: So, going back to literature, the first literary texts you published were poems that came out in Donato’s anthology?[14]

FZL: Not quite in Donato’s anthology. Amidst the attempts to search for funds to fight Macías, we published a few books that we called Guinean literature, or something like that; I can’t remember. That was how the first writings started to come out. Now I believe it’s been 25 years since those first texts that Donato, I and others published.

MR: And what is your opinion, in general, of the attempt to create a Guinean literature? Do you consider it important to label it that way?

FZL: Yes, I consider it important to label it that way because in this way, those of us who read in Spanish will realize that right now, the Spanish language has three legs. One is Spain: Madrid; Seville; the peninsula. Another leg is South America, and the third is in Africa. So it is important for us to be distinguished as such. You, as a good American, know that until something is named, it has no visibility. And you cannot make a movement. It is good, it is not bad.

MR: Do you feel that Guinean writers are obtaining more visibility?

FZL: The universities are giving them more visibility.

MR: In Spain too?

FZL: No, not in Spain. The Americans. Every time an American scholar calls me, I am unable to tell them no, because I know they are making a valuable effort, and people like Justo Bolekia, Ávila Laurel, and Donato Ndongo Bidyogo[15] know the dependence and the gratitude that we owe to the Americans. To American students. Because they have taken what we are producing very seriously with their theses and their studies. There is no American university where people don’t know something about what is being produced in Equatorial Guinea. And that is thanks to them, not to Spain. In Spain, they don’t give us the time of day. They haven’t fully understood that a small country called Guinea is the embassy of the Spanish language in Africa. And if they have understood it, they don’t care. But damn, for a continent that speaks a zillion languages to have a special part dedicated to Spanish? Even if the writing is shit! It’s true that sometimes I think to myself, geez, this novel is crap, or this poem has nothing interesting to it; but it’s in Spanish!

FZL: And Spain, the Instituto Cervantes and the institutions should be more aware of what is going on. Because you can’t imagine the number of people that write in Guinea; a ton.

MR: What is the situation for writers in Equatorial Guinea?

FZL: I’m not sure, because I don’t live there. But I suppose it must be frustrating because they don’t have readers. The government doesn’t do much for them. As Ávila Laurel said, “Writing in Guinea is like being a skier in the Sahara.”

MR: Yes, that’s what I imagined.

FZL: Yes.

MR: Can you tell me a bit about your upcoming literary projects?

FZL: I am preparing a book of poems. I want to call it, “Spanish Blue.” “Spanish Blue” is about language, religion, and the poetic relationship between my Spain and my Guinea. On one hand, blue represents the uniform of the Falangists, of the regime. The Falangist hymn said, “cover your chest in Spanish blue.” But then there is also a poem by Juan Ramón Jiménez that says, “Every afternoon the sky will be blue and placid.”[16] I love this “blue and placid.” And I think it’s a very intriguing thing. I have started writing it but I am not in a hurry.

MR: Very interesting. As a final question, have you ever thought about returning to Equatorial Guinea?

FZL: Yes, of course! I have to teach the kids to play soccer right, because I think they are doing it badly. And I can also teach them to play volleyboll, and I can also teach them to play basketball. And if the Guineans don’t want to, I can do it in Annobon. No problem.

MR: Thanks so much, Paco.

FZL: No problem, man. That’s two or three beers you’re going to buy me now, pal!

Footnotes

- The expression “Labyrinths of Memories” is a play on Zamora’s book of poetry, Memoria de laberintos. Madrid: SIAL, 1999.

- Malabo, the present-day capital of Equatorial Guinea, was originally founded under the name “Port Clarence” by the British in 1827. Its name changed to “Santa Isabel” upon restoration of Spanish sovereignty in 1844. In 1973, then president Francisco Macías Nguema renamed it “Malabo” in an effort to eliminate traces of European colonial influence.

- Just as “Santa Isabel” was the colonial name for the present-day city of Malabo, the present-day island of Bioko was known as “Fernando Pó” throughout the colonial era. Its name was changed to Bioko in 1979, during the Nguema regime.

- The Bubis are the predominant ethnic and language group on the island of Bioko (formerly Fernando Pó), where the capital Malabo (formerly Santa Isabel) is located. Mainland Equatorial Guinea is predominantly inhabited by the Fang ethnic group.

- There is significant tension between Fang, who represent a large majority of Equatorial Guinea’s population, and the Bubi minority.

- Zamora refers here to Francisco Macías Nguema, president and dictator of Equatorial Guinea from its independence in 1968 until 1979, whose regime is remembered for its extreme brutality.

- Zamora is referring to what is now known as the Plaza de la Independencia in central Malabo, which was known as the Plaza de España during the colonial period.

- Equatorial Guinea was declared independent on October 12, 1968.

- Germany hosted the 2006 World Cup.

- Ghana hosted the African Cup of Nations in 2008.

- Egypt hosted the African Cup of Nations in 2006.

- Angola hosted the African Cup of Nations in 2010.

- South Africa hosted the 2010 World Cup.

- Ndongo-Bidyogo, Donato, ed. Antologi?a de la literatura guineana. Madrid: Editora Nacional, 1984. Print. This was the first anthology of Equatorial Guinean literature ever published. Its editor, Donato Ndongo, is one of the best- known and most studied Equatorial Guinean authors.

- In addition to Donato Ndongo-Bidyogo, Justo Bolekia Boleká and Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel are other major figures in contemporary Equatorial Guinean letters.

- Jiménez, Juan Ramon. “El viaje definitivo.” Centro Virtual Cervantes. Web. 16 May 2014. <http://cvc.cervantes.es/literatura/escritores/jrj/antologia/antologia07.htm>. English version: “The Definitive Journey.” An Anthology of Spanish Poetry from Garcilaso to García Lorca in English Translation. Ed. Ángel Flores. Anchor Books, 1961. 279. Print.