The negotiation of identity looms large at the nexus of the colonial past and the postcolonial reality, and it is an important exercise for nations and citizens seeking separation and closure from the harmful and divisive legacies of colonialism. But there is a secondary process of separation too. This second separation involves becoming free from the literal and figurative mechanisms created to deal with the postcolonial reality. With the Arab Spring (also known as the Arab Uprising) in 2011, the world witnessed the citizenry of a group of countries in the Middle East and North Africa fighting to determine a future that was neither reactive, like the post-colony, nor externally administered, like the colonial past, but that was instead self-determined. It is this notion of self-determination that Scarlett Coten tackles in her exhibition Mectoub: In the Shadow of the Arab Spring.

Fittingly, Mectoub made its American debut at Seattle’s Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, which in an art scene that is particularly homogenous, stands out as a trailblazer. It exhibits artists hailing from at least thirteen countries and five continents many of whom are of African, Asian, and Middle Eastern descent, and/or deal with themes in their works connected to these regions. The gallery has established a practice that rejects aesthetic and conceptual narratives steeped in the European art historical tradition, in favor of discourse and praxis that support and promote diversity of experience and identity.

Coten’s Mectoub is the result of a discourse between photographer and subject, with Coten seeking to understand and document (mectoub means it was written, also destiny) identities other than what is considered ‘the standard’ (typically determined through a European lens). Coten’s decision to photograph Arab men bucks the global trend that focuses almost exclusively on the liberation of Arab and Muslim women who are framed as victims of an excessively oppressive Islamic patriarchy. Arab men are limited to caricatures of corrupt dictator, Muslim cleric or jihadist. Contrary to historical interactions between Westerners and Arabs, the men in Mectoub do not exercise their agency reactively. What we observe is a conversation. Coten asks “Who are you?” and these men respond assertively and unabashedly.

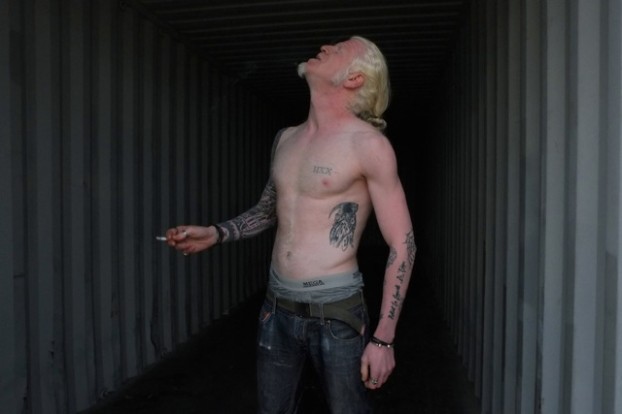

However tempting it may be to apply a Saidian analysis, the only, remotely Orientalist characteristic found in Mectoub is Coten’s French nationality. Mectoub is not the 19th century oft-salacious depictions of harems, bathhouses, and slave auctions. None of the men are dressed as devout, orthodox Muslims; thus a disassociation from Islam and the terrorist trope. Several are pictured bare chested, or with their shirts open in seductive, sexual poses. These postures could be interpreted as a nod to the odalisque genre of painting within Orientalist art however, the difference is that most of the men are looking directly at the camera and none of them are nude. When viewing the images, your eyes meet theirs straight away. The odalisque tradition portrayed fetishized female subjects: inanimate objects to be devoured by men. Coten depicts Arab men who are comfortable in their own skins, and who assert alternate gender and sexual identities over which the viewer, nor Coten herself, has no control.

To suggest these poses were elicited by Coten is too simplistic an assessment. It supports the antiquated concept of the colonial subject incapable of thinking for himself. Further, it implies homogeneity amongst a population of people with immense diversity. There are four main dialects spoken across the region, and while Islam is the dominant religion there are sectarian differences, as well as notable communities of Christians, Jews, Druze, and others.

Mectoub illustrates Arab men as proactive agents in the creation of their lives, their futures, and of their own representation. It effectively destroys the singular narrative that Arab identity is confined to patriarchal oppressive Islam and terrorism. In a space where the agency of these men is intentionally brought to the fore, these men illustrate self-determination that we must consider has always been there, hidden behind prevailing monolithic narratives of the region. There is a power shift at work here. When the western viewer is no longer the sole agent and consumer of the identity of a people it once subjugated, imaginably there is discomfort, dissonance and a rejection.

Footnotes

All photos courtesy of the Mariane Ibrahim Gallery