Article Photo Credits: Samira Idroos

The Play

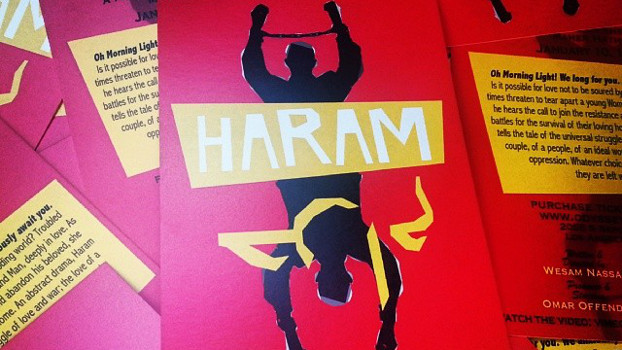

There are moments in history when a single word can represent an existential struggle between self-perceived opposites. Haram is such a word in our time. Haram, in Arabic, literally means forbidden. Functionally, what is haram in Islamic jurisprudential discourse is that which is not permitted for a Muslim. Examples in the religious context include eating swine, drinking alcohol and engaging in extra-marital sexual relations. In the tension between reformers and traditionalists, the term haram has come to encompass the linguistic battleground of ideas and ideologies.

Practically, determining what is haram brings enhanced authority. If something is deemed distasteful to current cultural trends, it is deemed haram; if it is not in the economic interests of governmental authorities it is haram; if it does not accord to a specific historical narrative of injustice, it is haram. In fact, the word has taken on many meanings and definitions among Muslims globally that belie its original one: things clearly articulated in the Qur’an as not permissible for Muslims. This debate led many reformers to take the path of deconstruction: engaging in linguistic analysis that matches the contexts of revelation and the reality of application. Communities of such scholars have fostered formidable movements for ‘another way of thinking’ about Islam and Muslim identity.

One such iteration of thought is Haram, a play written and directed by Wesam Nassar based on four poems and a short story written by Maher Hathout over a period of 59 years (he started writing them at 17 years of age). It was translated from Arabic to English by Syrian-American rapper and educator Omar Offendum. Performed at the Odyssey Theatre in Los Angeles to sold-out crowds, including legendary community leaders such as Rabbi Leonard Beerman, Haram serves as a benchmark for the collective development of Muslim American life in Southern California. Certainly, the role of art in modern Muslim life is a topic of great controversy among religiously conservative traditionalists. It is seen as a gateway for the practice of impermissible acts and desires. Rarely is a Muslim leader of Hathout’s prominence associated with public displays of art or public displays of personal intellection and emotional dissonance. It is even more rare for a formidable historical figure to share his youthful prose at the later stages of his life.

Many traditionalists argue that most modern genres of art are haram. The use of art to explore the complexity of Muslim identity in America is most clearly represented in Hip Hop music, which in and of itself is a counter-culture expression of art that is often opposed to establishment politics and power. Similarly, Haram can be said to be a counter-culture expression of art that aims to establish the revolutionary ideas of “knowledge of self’ and “freedom of authentic expression.” The world’s past, present and future are often most faithfully reconstructed by its artists and entrepreneurial pioneers of expression, as done in Haram.

Haram is a play based on words that were never written for public consumption, written by a man that lived his whole life in the public eye while attempting to shift paradigms in the public square. It is a mash-up of worlds and generations originating in 1955, from a then 17-year old Egyptian poet (Hathout) interested in looping his writing to a specific part of his favorite Mozart Concerto. More than half a century later he worked with his students Samira Idroos and Susu Attar (who produced Haram along with Offendum and Nassar) to lay those stanzas on that specific piece of music through the hands of Omar Offendum, one of Arabic-Anglophone Hip Hop’s most prominent poetic voices. This work represents a courageous act of love, and its creators are pioneers among Muslim American artists.

At its core, the play is about varying struggles in vying for love: the struggle for Egypt’s independence from British subjugation and colonialism, the struggle against nationalism articulated through the oppression of members of the budding counter-revolutionary movement at the hands of the Nasser regime, and the struggle to wrestle Islam from the hands of those that malign it through their violent actions or entrenched thinking. All of these struggles are juxtaposed with love. The love of a lover for her partner as he is pulled to join a struggle for justice, twhich is in its own right a love. The love of freedom, the love of fellow countrymen that leads a young revolutionary to risk the heart break of his lover for the sake of a better future for his people. At the core of the work, there is the love of justice.

As the lead character of Hathout’s short story says to his lover in defense of his desire to join a revolution: “Are you happy with this humiliating life? We live and die like slaves. Our voices silenced. We’re shackled with chains and ruled by violence. And you want me to stay quiet and continue to live humiliated like a coward?” The love for fellow revolutionaries here breeds a sense of solidarity, disallowing a man to be in bed with his love while his comrades are in battle for freedom. Yet this fidelity causes insurrection at home from his lover: “I’m going to cross the mountains to write our history, to make it a testimony for struggle. You see that as a crime? The crime is a life lived as a whim. It will melt away like something trivial, a mere delusion. And I’ll shroud it in my sorrow. So yes, my beloved, go ahead and hate me.”

In our time, it is still revolutionary for a Muslim leader to share poetry about love and war written in his/her youth through adaptations of students. Many religious leaders are accustomed to teaching what is to be memorized. They present a perfected (past tense) vision for others to ascribe to and follow. Hathout’s poetry being shared as adapted by his students stands in stark contrast to such tradition. Deeply personal poetry of religious leaders involving various intimacies being made public is quite revolutionary and diverges from the norm. Such departures cause unease. Haram is a display of co-creation and confidence in the journey of life to God perfected with companions and friends that are of similar orientation.

These very real tensions and their consequent roles in the revolutionary movements of his youth led Maher Hathout to a life of struggle that included imprisonment and torture. Unlike others, he and his brother Dr. Hassan Hathout, led a revolution of progress based in community with the aim of loving God’s creation and serving it for the betterment of all.

The Life, The Work

Maher Hathout was born in Shibin el Kom, Munufiyya, Egypt on January 1, 1936 in the same year that a boy named Farouk became King of Egypt at the age of 16 and assumed his role as the 10th ruler of the Dynasty of the Albanian, Muhammad Ali. Also in 1936, England and Egypt signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty giving more sovereignty to Egypt but maintaining a British military presence, opposed by General Gamal Abdel Nasser, later to become Egypt’s revolutionary hero and President. Hassan Hathout, Maher’s only sibling 11 years his senior, grew to become dedicated to the cause of overthrowing the British occupation of Egypt and expelling British troops from Egyptian life. This critical moment in Egypt’s colonial history was focused on national identities seeking to overcome colonial aggression and usurpation, and the emergence of nationalist freedom movements of varying stripes. From this world emerged some of the founding fathers of Muslim American Identity in Southern California, Maher Hathout among them.

Maher Hathout has exemplified passion, brilliance and faithfulness for thousands of families during more than 65 years of community service. As a founding leader of the Islamic Center of Southern California, he along with a cadre of visionaries came to establish the clearest articulation of a Muslim American identity to date. In his famous line, Hathout says “home is not where your grandfather is buried, home is where your grandchildren will grow and thrive.” Much of his legacy is in the area of giving Muslims (not just their leaders) a say in defining Muslim identity and the role of Muslims in modern contexts, specifically the American experience.

The challenges faced by thinkers that evoke ideas before the time of popular palatability has been significant in all generations, all communities and all ways of life. The transfer of ideas in Islamic intellectual tradition is no different. Scholars of Muslim history were killed or exiled for radical ideas, such as women leading congregational prayer, that destabilize power structures with vested economic interests in communal regression and oppression. Such is the difficult destiny of those that evoke ideas prior to a time in which they appear normative, out of touch with reality, as the scientist calling the earth spherical in a paradigmatically flat world. This dissonance encourages the students of those thinkers and those who lived with them to tell their stories, teach their knowledge, and preach their pedagogy. That secondary vocation, of student/scholar/artist as messenger is the necessary fulcrum allowing for migration of the original thoughts to a time more appropriate. This carrying of a message allows for the full actualization of the intentions of pioneering thinkers, and simultaneously allows the students to ascend in status to scholar. Throughout history, revolutionary knowledge has been taught in such a form. The creation and performance of Haram is an act that is part of this timeless tradition.

The Message

Hathout teaches that education and communal action are co-constructed between student and teacher. In my life with him I saw firsthand that he is first and foremost a movementarian. His primary concern is sustaining movement and the health of The Movement. He believes that organized work is the only way to bring about sustainable change in destructive thinking patterns and patterns of action. It is always about the work coupled with a strong ethic in critical thinking and developing a consciousness of the suffering around us all.

As the curtains closed on the first performance of Haram, with Hathout in the audience, the question and answer session included all actors, producers, and the director. In that discussion it was clear to everyone that Haram was meant as an encouragement from a leader to his comrades to “continue the work that we started together.” As such, Haram is a work of love and collaboration by the students of Dr. Maher Hathout.

Who said that poetry is speech? Poetry is a fleeting moment of sincerity. Poetry is an emotional sentiment poured into the artery of a letter. For letters are Godly light. And a word is a world of dreams. Uninhibited by the wall of fear. For if the fear has to conquer the word. It should be sheltered behind silence. So let us remove sound from our tongues. And intonate without speech. And shake hands without greetings. For if the word is robbed of honesty it will sentence it to death. And I my friend do not tire. I am a poet of truth that does not lie. I am a knight of poetry that doesn’t get defeated. Silence that is articulating is not a loss. But counterfeiting melodies by the crucifying of one letter next to another. To create false intonations. Trembling from fear. And I, my friends, am a poet. Searching for another language. Undetected by the eye of the monster. With silence I say: One look from my eyes ignites. One quiver of my lip pronounces hot coals. And with the sword of silence I slice and dice. In my daydreams are verses that will flabbergast. When I lower my head in silence, it is poetry imprisoned in me. In my gasps I light aflame with poetry. And my sighs. If you do not understand, do not speak. Do not delude yourself into thinking I have died. For tomorrow I shall unwrap the covers of silence. From the sweetest fruits of melodies. From poetry that is not burdened by death. As I write in verse. The truest of human emotion. The word stretches to its fullness. It does not cower in fear of monsters. Until that time comes. Articulated silence is not laziness. Silence is eloquence. Silence deafens with a thousand bells. Silence is the piercing weep of lament. If you do not understand do not speak. Let he who is ignorant of my language leave me alone. Don’t assume this to be fatigue. For the poetry which is embedded in my silence can only be understood by the wise.

– The Language of Silence, Maher Hathout (1955) as translated from Arabic by Omar Offendum.

Article Photo Credits: Samira Idroos