The artist Peter Clarke was one of the first people I met on my arrival to Cape Town. As I remember it now, the impact of the quiet, careful elder who regarded me with experienced eyes was my warmest welcome. While one hand caressed a glass of red wine, the other he offered to me in greeting. It was 2010, before the start of a performance at the Fugard theatre. Several people were gathered around Clarke, and it was simply good fortune that led a mutual friend to introduce me to the artist.

The well-known artist’s warmth, kindness, and humility caught me by surprise. I was younger by nearly six decades, but he patiently listened all the same as I introduced myself, and briefly explain that I was in South Africa to work in the arts. A glimmer of a smile appeared on the face of the elder artist as he offered some words about the art scene in his Cape Town. When he finished, he nodded and turned toward a waiting friend. He then paused and turned back, saying: “Here, take my card and we’ll talk some other time. I’d like you to come visit and see my artwork.” Turning the card over in my hands. For a moment my young self was surprised to find only a street address and telephone number; my reflex was to look for an email address to which I could write. When I looked up again, Clarke’s spry frame was heading into the theatre. We just met, and Clarke’s warmth went beyond a simple welcome as he invited me to share his vision of South Africa.

Before continuing, I should note the stimulus for my meditations here is Clarke’s passing in April of 2014. Born in 1929 in Simon’s Town, The Group Areas Act moved him to Ocean View in 1973, and he lived and worked there until his passing. Clarke is best known for his paintings and prints of the daily life of Cape communities, but for decades he also quietly produced collages, handcrafted concertina books and poetry.

Clarke’s biography is astounding. The artist was relocated in the forced removals from Simon’s Town to Ocean View. He began his artistic career as part of community arts programs, and his sense of community and he maintained his commitment to public arts programs and social engagement, for many decades. Whereas most other now well-known artists of colour fled South African oppression, Clarke remained in the country. For instance, Gerard Sekoto thrived in France while Clarke survived in Cape Town. Clarke has engaged notions of ‘space’ for many years. The artist’s commitment to live and produce from his home base is a decision that is both personal and political.[1] It was from South Africa that Clarke developed and nurtured global community. These networks are both physical and conceptual, and the artistic engagement motivated active dialogue with artists internationally, among artists of colour in particular.

Since Clarke’s transition, several thoughtful eulogies have appeared. Emile Maurice marks the artist’s status as ‘elder statesman’ while Mario Pissaro is more direct in his description: “Peter Clarke was, indeed is, a giant.”[2]These authors (and others) offer broadly panoramic surveys of the different modalities in Clarke’s life and artwork, and Pissaro is especially attentive to the criteria and modes of interpretation that are employed to historicize Clarke’s activities. Indeed, it is difficult to overstate Clarke’s impact on histories of South African visual art.

Clarke’s work has appeared in several major exhibitions that solidify the artist’s relevance on both popular and critical levels. Clarke had been exhibiting work since the 1950s, and in 2011, Patricia Hobbs and Elizabeth Rankin produced a major retrospective exhibition and book on Clarke’s work. The venue of the South African National Gallery and its production by Standard Bank Johannesburg makes the project a definitive comment on Clarke’s oeuvre. In 2013, Michael Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town held an exhibition and produced a catalogue of Clarke’s work, and in the same year Riason Naidoo and Tessa Jackson curated the first major exhibition of Clarke’s artwork in the United Kingdom at INIVA.[3]

In this brief reflection I shall be adopting a less panoramic viewpoint, and setting aside some important insights relayed by others, for example, Clarke’s mood that day in 1956 when he decided to be a full-time artist, or the specific ways in which the German Expressionist art movement influenced the artist’s style. Instead, I shall be focusing upon more theoretical issues in Clarke’s history and reception.

I would like to introduce Clarke’s unique position as an artist, including his impact on the development of critical discourse over decades. The artist’s long life afforded him reciprocal vantage points, shaping a historically informed awareness of the present day. Within the scope of this brief essay, I can do little more than gesture at the wider context that I believe to be necessary in formulating Clarke’s impact. I should say my tactic is to give some weight to what this impact might mean as a demonstration of visual culture in South Africa, of looking and being looked at, of spectacle and spectatorship, and the staging of the quotidian. I also make no apology for discussing the essential drama of black life, and what any of this has to do with the quintessential modernity of Clarke’s practice. I hope this viewpoint will provide an alternative way of framing the biographical picture that others have, quite rightly in my view, judged to be important.

My attempt to reflect on the vibrantly beautiful pictures of Clarke’s oeuvre immediately refracts in the glare of South African historical fact. The advent of Apartheid in 1948 merely ‘hardened’ a model for white minority rule in Africa that derived from nineteenth century British colonial policies—including the removal of African families from their farms; segregating spaces in cities; restrictions on mobility, sexual freedom, and economic rights of non-white South Africans, including the Pass Laws Act of 1952, which formalized the mandatory reference book identity document.[4] The catalogue for Clarke’s 2013 exhibition “Just Paper and Glue” points to this history; the second page pictures Clarke’s identity document issued in 1989, complete with photograph and biographical details. As a collage element, the inclusion of this fragment points to the legacy of the legal, psychological and social effects of the colonial era. What is more, it underscores the longstanding impact of these effects on daily life and interactions between people, going so far as to shape the space of imagination.

Space is materially and conceptually paramount in Clarke’s artwork, and the artist addresses the concept through a variety of media. Early pictures included views of his surroundings in Simon’s Town and the ocean shoreline. Clarke’s catalogue of landscape paintings provides literal examples of the artist’s concern with space. Clarke notes: “One idea, one project I’d like to see take shape is: I’ve always been interested in space, you know, space, space, space, and also in what happens in space, a space like this…”[5] The consistent genius in Clarke’s “space of imagination” may be its ability to depict and metaphorize at once. Gavin Younge picks this up with an incisive observation about Clarke’s “Haunted Landscape” (1976), describing it as a picture that represents a ‘landscape of the mind.’[6]

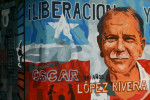

In an artwork made in gouache and collage titled “Afrika which way” (1978), the landscape view is interrupted and blocked by a white wall covered in graffiti. The space is divided in thirds, against dark grey clouds, in the upper left and right, a blue sky at dusk mingles with magentas, purples and blues. Hovering in the upper right of the scene, above the dividing wall, a setting vermillion circle is collaged over the clouds and placed above the wall. This picture is overtly political—the graffiti references Africa’s liberation leaders including Amílcar Cabral, Kwame Nkrumah, Jomo Kenyatta and Julius Nyerere – and attacks the Cold War that was tearing southern Africa apart. Clarke comments:

Among the various laws that were put into place by the apartheid government was the Group Areas Act, whereby they would remove black people out of town in order to create separation between one group and another. So that people in Simon’s Town, people who had been there for a very very long time, people who’s parents had been born there, grandparents and so on and so on, they were given this order that they would have to move out, and they were in fact moved out of town… And so I became interested in this thing about graffiti, protest, space.[7]

A black dog trots along the fence as if to exit the scene, and in the vibrant, warm hued foreground, a young black man holds a birdcage from which two white doves fly. In this landscape, text and collage are in the mid-ground—at the center—of the image.

The iconography of these details matter to the (un-isolatable) formal properties of Clarke’s artwork, yet here my move is to establish some procedures to trace a relationship between Clarke’s longstanding admixtures of picture and text, visual practice and community outreach, and a courtship with conventional visual forms of European modernism as it consistently appears with local and necessarily black African (and Diasporic!) subject matter. This brief essay will only preview the wider context necessary in formulating such an issue. Here I give some weight to specific, if diverse points, but place the main emphasis on understanding the overall logic that links Clarke’s oeuvre to vital moments, concepts, meanings, and historical legacies.

From the fifteenth century the region posed an environmental conundrum to Europeans. From the early, dismissive assessments of the Portuguese to the Dutch colonizers of the region from 1652 to 1799, to the British controllers from the nineteenth century, the form and concept of the landscape was a problematic inheritance, as much so as the indigenous populations found therein. The Cape came to be populated by a mixture of indigenous inhabitants and colonists that spoke European languages but—because of unique cultural exchanges and makeshift colonial lifestyles—refused to act out the modes of life expected of them as ‘Europeans’. After 1880, the region was propelled into industrialization and by the geopolitics of imperialism transformed into an autonomous, modern society.

Closely related to the geopolitics of industrialization was the emergence of aesthetics, an attempt to develop a consequential science of appearances and imagination. The practice mediated the emergence of the modern representation, and initiated a shift in art away from the poetic tradition of classical mimesis toward “abstraction” and “non-representation.”[8] This is the bare minimum we need to note that to think about ‘landscape’ and ‘environment’ is to be concerned with describing “something there,” which is one among many questions of representation, the same methods that mediate the construction of imagined communities, nations, and personal identities. Geographic territory defines national identity through two distinct ways of understanding: internally, how the national community is imaginatively linked to the land; and externally, how the community is delimited in relation or in contrast to other groups in proximity.[9] Put another way, there is a direct link between space, land, territory, community and identity.

During the twentieth century, the preoccupation with finding some kind of psychic accommodation with the land became a defining feature of white South African nationhood. Apartheid’s ‘hardened’ model for white minority rule in Africa extended nineteenth century British colonial policies that included the removal of African families from their farms; segregating spaces in cities; restrictions on mobility, sexual freedom, and economic rights of non-white South Africans—black people—of various skin colours. Fred Moten insists the history of blackness is testament to the fact that objects can and do resist such debilitating restraints on the imagination, and Clarke’s visions provide specific examples.[10] Clarke’s artwork offers ways of seeing how race and power have been legitimized and naturalized by everyday practices and experiences. Here, the basic point is that ideas about space and place are embedded in and produced by modern and transnational networks of knowledge and discourse, and Clarke’s wisdom allows us to see this movement.

In returning to “Afrika Which Way,” herein is a demonstration of visualizing landscape to invoke space, but also to use of text and collage as forms that execute disruptions of the established order. Clarke states this plainly:

I’m interested in recycling of materials, trash, leftovers, etcetera. I like to think in terms of the world being cleaned up and so I am doing my little bit for the process by making use of stuff that should be dumped, or is dumped and then retrieved, and so on. So I’ve made lots of use of collage… so its making use of waste materials in other words… what else?[11]

Collage in the usual meaning involves the pasting on of scraps that originated beyond the studio, in the store or on the street. The French noun coller means literally to glue or to stick. Collage method impacted the formation and elaboration of the art historical style known as Cubism. There was composite imagery before the twentieth century, but the appearance of collage in European modern art was substantially new.[12] Collage is linked to notions of indecency, paradox and perplexity—as “impurity by any other name,” and this technique of pasted paper had a special and profound part to play in the expression of the Modern sensibility in Europe and beyond—a sensibility tuned to matter and “capital” in the modern city.

Returning to historical fact: early papiers collés heralded in the Spanish artist Picasso’s involvement with “African art.” Picasso’s surrealist and cubist works are described as representations of representation. They are, like language, structured by means of arbitrary signs ‘circulating’ within a system of opposites. In collage, even when the imported object is still whole (a newspaper clipping, for instance), it has to join another surface where it does not strictly belong. Things happen in this transfer. A new relationship is enacted between the ‘low’ culture of newspapers and magazines, and the ‘high’ culture of professional art. This relationship is ‘inappropriate’. The collage method, then, delivers visual and conceptual encounter. Indeed, something happened in the explosive encounter between the European artist and the Trocadéro museum in Paris where non-Western artifacts were displayed and stored.

The collage method pulls the viewer in different temporal, conceptual and material directions when looking at the picture. This matters to Clarke’s artworks because this perspicacious feature articulates a vibrant modernity—of the discarded, unwanted, or overlooked as much as that which is kept, cherished or convenient. Collage in the fine arts allows viewers to see that it is somewhere in the gulf between the bright optimism of the official world and its degraded material residue, that many of the exemplary, central experiences of modernity exist. The fissures that open from a foreclosed universality, a refusal of humanity, a heroic but bounded expression, is black creative production.

Clarke’s use of collage and text begin to extract a new horizon of possibilities from within the moral and epistemic contours of a “postcolonial” present. Clarke inserted himself into the evolving discourse of modern African art during the 1960s.[13] Whereas Picasso used collage to escape narrative imagery, Clarke fills his scenes with text and signifying marks, situating them in space.[14] Such a process that orients and situates our selves in space while coming to know the surrounding environment seems indispensible to the recognition of the self as a self.

Modernity’s fragments, some suggest, are its history, its residue, what is left over when consumption has ended for the day, when trading and exchange have ceased and the people have gone home. The production of blackness is a feature of the extended movement of modernity’s specific upheaval. It is a strain that pressures the assumption that personhood (personal biography) is the equivalent of subjectivity.[15] Put another way: since the colonial era, black South Africans have been portrayed as commodities who spoke—as laborers who were commodities before, as it were, and the abstraction of labor power from their bodies continues to pass this material heritage on, across conceptual divides that separate slavery and “freedom” in time and space.[16] These ideas may be placed in metaphorical relation to an artwork Clarke describes:

I have a feeling that in a space like this, If there is an air current coming in from that window or another source, and then another, and there is a current coming in from somewhere else, like over there, what we can’t see is what is happening with these particular streams of air. I have a feeling that if colour could be introduced into these streams, different colours, it would be visible, we would be able to see what was happening in these different streams, we would be able to see movement.[17]

Clarke’s work offers an opportunity to see movement in our aesthetic-political present. On the one hand, it asks what is demanded of a practice of postcolonial, postapartheid creativity. On the other, it asks what postcolonial creativity’s demand on this present ought to be.

Assuming, as I do, that the answers to these queries are not transparently self-evident and not adequately covered by the dominant vocabularies of the art historical, cultural and political realms we currently inhabit, Clarke’s artworks are one way of beginning to formulate responses to such questions.[18] Clarke’s oeuvre prompts us to see movement, to ask how, and with what conceptual resources, do we begin to extract a new yield, a new horizon of possibilities, from within the moral and epistemic contours of our present moment, and beyond.

Footnotes

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sUOjys0cIlU

- http://africasacountry.com/the-work-of-the-late-artist-peter-clarke/); (http://asai.co.za/artist/peter-e-clarke

- http://www.iniva.org/exhibitions_projects/2013/peter_clarke

- John Peffer Art and the End of Apartheid (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press 2010) xvi.

- Stevenson, Obrist, http://www.stevenson.info/publications/clarke/paper.html

- Gavin Young “de arte” no86 2012 (http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/dearte/dearte_n86_a13.pdf).

- Peter Clarke “Just Paper and Glue” Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. Interview by Hans Obrist http://www.stevenson.info/publications/clarke/paper.html.

- Jeremy Foster Washed with Sun: Landscape and the Making of White South Africa (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2008), 6

- Ibid: 16.

- Fred Moten In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 14

- Clarke in “Just Paper and Glue” Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. Interview by Hans Obrist

- Brandon Taylor Collage: The making of modern art (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2014)

- Mario Pissaro (http://asai.co.za/artist/peter-e-clarke), April 2014.

- It was primarily through collage that the artist could maintain a relationship to commercial modernity that was philosophical and social in the broadest meaning of those ill-fated terms: sometimes satirical and parodic, but also reflective, aesthetic and above all experiential. On another level, collage deliberately evoked the cognitive and technical standards of the child, the playful, or the mad—suggesting that anyone can shape material this way—that anyone can practice in the field of the fine arts. In Collage: The making of modern art (New York: Thames and Hudson 2014), 9.

- Moten writes: “While subjectivity is defined by the subject’s possession of itself and its objects, it is troubled by a dispossessive force objects exert such that the subject seems to be possessed—infused, deformed—by the object it possesses.” Moten 2003, 14.

- Ibid, 6.

- Peter Clarke “Just Paper and Glue” Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town. Interview by Hans Obrist http://www.stevenson.info/publications/clarke/paper.html.

- On the issue of future thinking in the circumstance of postcoloniality, see David Scott Refashioning Futures (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999)