Abstract

Through a journey on a Mexican “tourist bus” from Mexico’s southern to northern border, this article traces the influence of the U.S. border security framework on Mexican sovereignty and migrant insecurity. The article reveals the continuity between the current border “crisis” and past moments of border and immigrant anxiety. While clamors for security have been marshaled to justify enhanced security measures, the results are often an increase in corruption, insecurity, and human rights violations.

Key Words: Border security, immigration, human rights, Mexico-Guatemala border

Nearly every block of the former sleepy colonial town of Frontera Comalapa, Chiapas, Mexico now hosts a “Travel Agency”, which advertises trips to Tecate, Baja California, Altar, Sonora, and Tijuana, Baja California. If you have ever been to any of these places, you know they are not generally considered to be vacation destinations. A few miles away in a dusty lot, buses line up Wednesday mornings to proceed to the northern border, a trip that takes three days and three nights.

Image 1: Bus stationed in Frontera Comalapa, Chiapas, Mexico in expectation of a journey to the U.S.-Mexico Border. – Photo Credit: Rebecca B. Galemba

Mexicans ride these buses, but Central Americans also seek to blend in. At the southern border, a history of cross-border marriage, social networks, and refugee flight and return during the height of Guatemalan counterinsurgency conflict (1980-1981) make distinguishing Mexicans from Guatemalans difficult. Mexican adults in the region told me that most could not trace their families any further back than their parents or grandparents to Mexico. They all had Guatemalan roots. Yet Mexico’s official attitude towards such fluid identities is anything but. In this region many poor residents lack documents and the border has been historically porous. Meanwhile, at the southern border, the municipality of Frontera Comalapa has developed into a hub to purchase any document you want. Official surveillance in this context often takes on ethnic and classist tones. I asked one immigration official how she could ascertain the difference between Mexicans and Guatemalans in this context. In addition to dress and dialect, she mentioned, “we can often detect by the smell.”

One February day in 2007, I purchased tickets for this trip at a “Travel Agency” in Frontera Comalapa. I was not planning to travel until the end of March; advance purchase did little to secure my reservation. When my husband and I attempted to travel north on one of these buses one March Wednesday morning, many buses refused to let us board. Operators claimed they were full. While some buses were hired directly by maquilas, or border assembly plants, at the northern border, it was also clear that many were neither full nor contracted. What I learned from the one company that allowed me to ride was that many were wary of human rights reporters. I had bought my tickets to Tijuana, where I intended to visit contacts from field research in 2004. While many people said they were going to Tijuana, in reality few buses had Tijuana as their destination. The drivers told immigration agents they were headed for Caborca, Sonora. Only as we approached the border did I learn that the bus was destined for the desert border town of Altar, Sonora. Why were these buses so openly advertised, yet also disguised? A Mexican bus operating in Mexican territory should be free to operate without fear. The tourism or travel label was partly designed to get around Mexican bus companies’ monopolies over particular routes. Yet this label also disguised the purpose of the journey since a deeper suspicion of illegality surrounded the buses due to their destinations and passengers. This bus ride from Mexico’s southern to northern border provides a window into how Mexico is implementing border security through interior checkpoints, as well as to how the U.S.’s security agenda casts a specter of illegality over these buses and their passengers even within Mexican territory.

—-

This piece focuses on the problems of trying to prevent undocumented migration to the U.S. by investing more resources and assistance into Mexican border policing in order to fulfill a U.S.-designed security agenda. Mexico has recently escalated border enforcement to stem what the U.S. termed a “border crisis” of undocumented Central American youth arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2014. In July 2014, Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto implemented Programa Frontera Sur (Southern Border Program[1]) to improve border security and to protect migrants entering Mexico. To solve this crisis, according to many politicians and dominant media renderings in the U.S., Mexico must enforce its own southern border. U.S. assistance is implicit and explicit in this solution as the U.S. embraces Mexico as a key partner for establishing hemispheric security (Benítez Manaut 2003). Alan Bersin, U.S. Assistant Secretary of Homeland Security recently stated, “The Guatemalan border with Chiapas is now our southern border” (Isacson et al 2014: 5). Recently, Mexico’s Secretary of the Interior Miguel Angel Osorio Chong similarly articulated Mexico’s “new” approach to the border, “Never before has Mexico announced a state policy on the border… now [it is] absolute control of the southern border” (Archibold 2014). Yet these statements are somewhat misleading while they also lack historical depth. The southern border has never been consistently well patrolled, but periodic crackdowns have been common throughout Mexico’s recent history.

This article reveals the historical continuity that the discursive construction of a “border crisis” has played in justifying increased, yet often ineffective, counterproductive, and perhaps even destructive, border enforcement. As recently argued by Gabriella Sanchez (2014), the construction of a “border crisis” is a powerful narrative to justify the escalation of criminalization, militarization, and violence.[2] It entrenches the political status quo: fear of a “crisis” derails immigration reform and justifies more resources for controversial U.S.-backed Mexican and Central American security initiatives. In this narrative, enforcement, rather than human rights, the right to mobility, and the failures of broken immigration and labor systems, becomes the dominant policy and media focus.

The justification of heightened security to combat a purported border crisis has older roots. The suspicions and surveillance surrounding this bus’ journey, for example, highlight Mexico’s subservience to the U.S. border agenda seven years prior to the 2014 crisis. To claim that a crisis has simply emerged obscures the ability of historical analyses to temper current approaches and to offer alternative solutions. Specifically, the crisis discourse, and the enforcement policies it legitimizes, shares much in common with the U.S. approach to the U.S.-Mexico border, which became especially prominent during the 1980s War on Drugs and the 1990s border enforcement built up.[3] Peter Andreas identifies the similar power of the narrative of “loss of [border] control” at the U.S. Mexico border. According to Andreas (2000: 7):

The stress on loss of control understates the degree to which the state has actually structured, conditioned, and even enabled (often unintentionally) clandestine border crossings, and overstates the degree to which the state has been able to control its borders in the past…it obscures the ways in which the state itself as helped to create the very conditions that generate calls for more policing.

In the historically porous Mexico-Guatemala borderlands, the rhetoric of border security has intermittently risen to the fore to justify increased surveillance; state officials have often used ethnicity and dialect to signal otherness and exclusion.[4] Mexico first militarized its border with Guatemala to contain the refugee flow during the Guatemalan conflict in the early 1980s (Cruz Burguete 1998). More recently, Mexico intensified border enforcement and interior inspection points in line with a U.S. post-September 11, 2001 hemispheric security agenda. In July of 2001 under Plan Sur,[5] Mexico signed onto a U.S.-backed plan to not only strengthen its southern border with Guatemala, but also to implement militarized internal checkpoints. According to Miguel Pickard (2005), “the measure had the effect of ‘displacing’ tasks of the U.S. southern border to southern Mexico.”[6] Plan Sur increased migrant vulnerability as migrants sought out more dangerous routes and sophisticated smugglers to avoid the checkpoints (Birson 2010). Migrant desperation has become lucrative for cartels and criminal gangs who bribe their way through the bolstered security system (Birson 2010).

—–

On the bus, the mood was light as passengers joked with one another, music switched somewhat seamlessly between Mexican Norteña bands and Britney Spears, and passengers requested different DVDs. Some DVDs were bootleg copies of comedies; bus passengers laughed when the amateur bootlegger also captured audience members walking in and out of the theater when trying to film the actual movie. Most of the DVDs did not even have Spanish subtitles. However, most passengers seemed content to focus on something else besides the barren hillsides. The bus journey, however, was impeded by multiple checkpoints staffed by immigration, customs, the police, or the military. Checkpoints were more frequent at the southern border in Chiapas and again, as we neared the U.S.-Mexico border. At each checkpoint, the atmosphere shifted as passengers were instructed to get off the bus and to file into separate male (over 40 individuals) and female (4 individuals) lines as their papers, faces, and ways of talking were inspected.

Outside of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, we came to a temporary inspection point in the form of a tent set up on the side of the road with a small plastic table for food and a television. An immigration agent boarded the bus yelling, “Gather of your belongings [when you get off]. Please gather all of your belongings.” She didn’t give anyone time to speak. We were never given a reason why three men were kicked off the bus after the agents inspected every passenger. The agents suspected that the men were Central Americans. One passenger, who others referred to as their “guide” or “boss”, urged people who knew the men to defend them, but many people were afraid that this would render them suspect as well. One passenger told me that he was traveling with five friends, but that two were from Guatemala. The men told officials at the Mexican checkpoints that they were traveling separately because, as the passenger explained, “I don’t want to be accused of being a coyote [human smuggler] if they [Guatemalan friends] are caught. We don’t want to be associated.” He continued, “Sometimes Mexicans are being taken [off the buses] at the checkpoints while some Guatemalans pass fine. They [officials] will confuse [Mexicans] as being Guatemalan. It is very strict now.” Sometimes people were unsure if others were Mexican or Central American. The above passenger was uncertain, “They are from Guatemala, but have lived in Mexico for a long time. They are more Mexican.”[7] The “guide” believed that the men were Mexican and that the immigration officials “just want money. They often behave badly. If they have money, the [officials] will let them pass. They [officials] don’t have the education to know who is Mexican and who is not. They also don’t seem to care.” He continued to explain that people “often do not know how to defend themselves…Even when they are Mexican, the migra [immigration agents] will remove them [from the bus].” The three men had been taken off of the bus, but at later checkpoints, officials instead collected money from individuals or from the bus drivers who then collected from the corresponding passengers. Some men told me they believed that people who anticipated a problem could sometimes pay an advance fee to the bus drivers to help them through checkpoints. One man told me that he refused to succumb to this practice; “If you don’t pay, they take you off the bus…[But] I am Mexican and I would rather get off the bus than pay.” When this man was stopped for further questioning at one checkpoint, he related, “They asked for everything, all my documents…” He laughed…“And then, what are my parents’ names, how old are my parents, where was I born, how old am I, what day was I born, why did I leave? …If you answer just one question not to their liking, they take you off the bus.”

Ironically, Grupo Beta,[8] a Mexican unit dedicated to protecting migrant rights in Mexico, stopped the bus a few miles after the men had been removed from the bus by immigration. As they delivered pamphlets addressing the right of Mexicans to travel freely within Mexico, we recognized the terrible irony that the men had just been kicked off the bus. A Grupo Beta representative inquired if any immigration agents had asked for money from anyone or if anyone had been kicked off of the bus. They told the passengers that no one should be able to infringe on their rights to travel as Mexicans or to take money from them; if this occurs, then they should report it. Yet, the passenger who identified as a “guide” explained, “If you are Mexican you can go to human rights, but it’s often too late. They [human rights] should be watching the migra since it is complicated to denounce them. But they [human rights] are often located where they cannot do anything to resolve anything. Then you lose time and money.” When passengers mentioned that three men had just been kicked off of the bus, the Grupo Beta representative responded, “If you know they are Mexican… from your communities, defend them.” Yet the representatives also admitted that this could lead to problems since they knew that many people carried false documents and “if you do not know, you can be accused of being a coyote.” The potential for illegality rendered all passengers vulnerable to the whims of authorities operating under a U.S. security lens that is suspicious of all travelers heading north. Surveillance in northern Mexico is often racially marked against not only Central Americans, but also against southern Mexicans and the indigenous, who northern Mexicans have historically stigmatized as backwards and as posing a potential threat to the socioeconomic order (Vila 1999: 80).

As we approached the U.S.-Mexico border, the bus drivers gave gifts of DVDs and cigarettes to immigration inspectors to ensure a smooth passage through various checkpoints. The drivers knew the agents well; then the agents would wave, “see you next week.” As we neared the border, the bus drivers also urged passengers to hide their cell phones in overhead compartments. They knew officers might confiscate phones since they suspected they would be used to call coyotes waiting at the border. Some passengers had made the journey to the U.S.-Mexico border in groups and planned to call coyotes to help them with the long trek through the desert into the United States. Less experienced passengers were accompanied by the Mexican “guide” on the bus, whose task was to deliver them at the U.S.-Mexico border to a partner more familiar with the next leg of the journey. When we arrived in Altar, Sonora, everyone got off the bus and seemed to disappear into the desert dusk. My husband and I entered one of the few taquerias in an otherwise desolate town to wait almost two hours for a bus to Tijuana.

The bus journey illustrated the unpredictability of surveillance and the anxieties, as well as opportunities, this generated for passengers. Immigration agents might detain and deport someone, collect a bribe, or choose to ignore or fail to recognize false documents. While many bus passengers were apprehensive about the journey, more experienced migrants knew that they would eventually succeed. One passenger who was friends with the men who had been kicked off the bus received a phone call from them as we approached the U.S.-Mexico border. His friends would be joining him at a hotel in Altar, Sonora to wait for their coyote.

The Mexico-Guatemala border has long been selectively and unpredictably enforced. The actual official border is often easy to cross. At an official inspections post at Ciudad Cuauhtémoc, Mexico and La Mesilla, Guatemala, I often found confused tourists wondering where to get their passports stamped when they crossed the border. Border officials generally remain in their offices as people easily walk across the border and board vans to their destinations. However, semi-permanent, as well as unpredictable, checkpoints increasingly break up interior highways. Makeshift checkpoints may emerge overnight and vanish the following day. However, at the same time, a lack of sufficient and trained personnel, historically porous flows, the necessities of trade, and the fact that border security is costly and often counterproductive, lead the government to promote one image—of total control—while the reality is otherwise. As one customs official explained, “There are only 30 fiscal inspectors in all of Chiapas. Look…[he beckoned out of his office window to the expanse of mountains that constituted the international border]. This is a big state. With only 30 [inspectors] what are we supposed to do?” Unpredictability at once engenders fear and hope, which fuels the ability of corrupt state officials and smugglers to take advantage of migrants. Meanwhile, an image of control, rather than its actual implementation, enhances state legitimacy by demonstrating the state’s commitment to border management (Andreas 2000: 11; Nevins 2002). Similarly, at the U.S.-Mexico border, Peter Andreas (2000: 9) argues, “successful border management depends on successful image management, and that does not necessarily correspond with levels of actual deterrence.”

One customs official in Chiapas explicated the function of the image of control:

What the government wants to do most is show an image of control…but of course…if you actually see, you know that isn’t true…To actually exert control costs…the government is often not willing to spend the money…The government has sent more forces, but they are the same….They could send ten more units and it would be the same.

This disjuncture between image and reality has proven true in the past; when Mexico created a new border police force (Policía Estatal Fronteriza-State Border Police) in 2007, border residents I knew soon realized that many of the officers were the same men they knew from the state police force. The officers had received new uniforms, but otherwise nothing had changed. This buildup of the border security apparatus is a product of the state’s desire to show a public presence of force, while simultaneously realizing the inability, and impracticality of, fully controlling the border (Andreas 2000).

Recently numbers of undocumented migrants at the U.S. border have declined and the rhetoric of crisis in the U.S. media has subsided. However, Mexico continues to confront much of this flow. A priest who works with the Casa del Migrante in Tecún Umán, Guatemala told me in 2007, “To work for immigration is dirty work…Bush asked Mexico to help detain migrants going north and Mexico is doing its dirty work.” According to Migration Information Source, Mexico has deported over 30,000 Central Americans in 2014 (Archibold 2014). Can this really be termed a successful solution to a crisis? When migrants are caught within Mexico’s web of enforcement, they’re more likely to be preyed upon by gangs, officials, and cartels, especially in border cities where migrants may desperately wait, become stranded, or try to gather funds to try again or return home. The hostel worker related, “And from these same migrants the officials feed themselves, taking their money and then they are allowed to proceed.” One migrant described the symbiosis between migrants and officials, “If there weren’t migrants, the migra [immigrant agents] would not have jobs. The migra are corrupt, they take your money and beat you.” To him, officials and bandits belong on the same continuum. He was deported because he had no more money to pay officials-the maras gangs had already taken everything.[9]

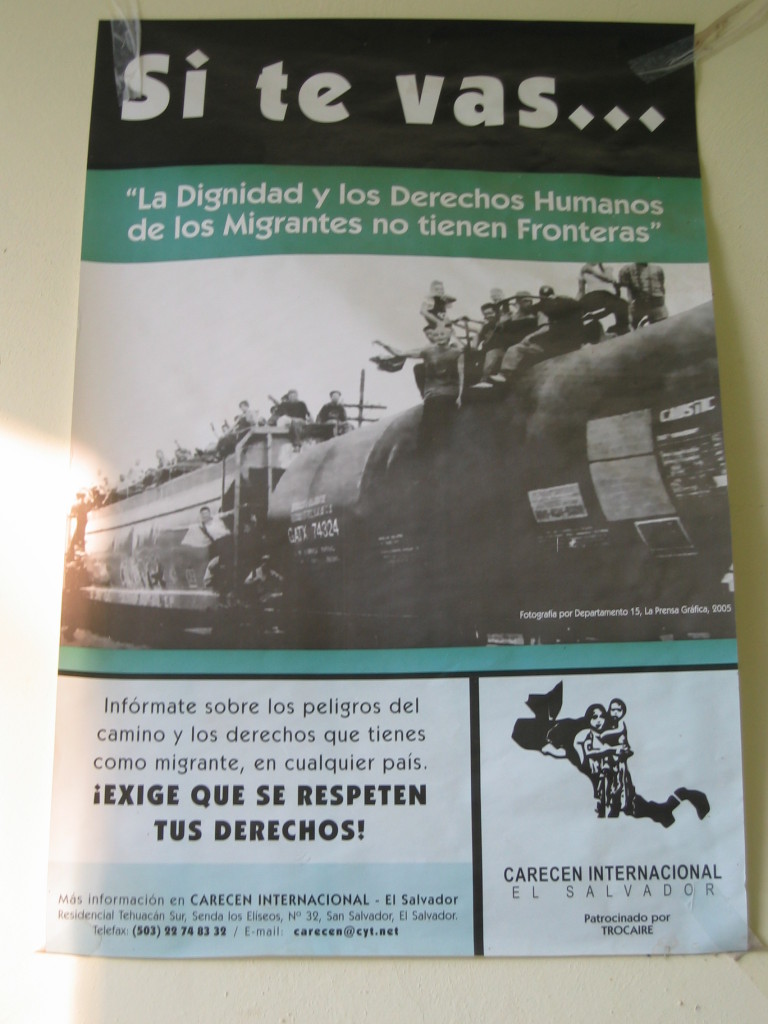

Mexico recently committed to patrolling the freight train called “La Bestia”/ “the Beast”, which migrants jump on and cling to as they attempt to make the journey north.

Image 2: Flyer warning migrants of the dangers of “The Beast” if they decided to travel north. Translation: “If you go… ‘the dignity and human rights of migrants do not have borders.” – Photo Credit: Photo taken by Rebecca B. Galemba at the Casa del Migrante in Tecún Umán, Guatemala.

In Tapachula, Chiapas, I met double amputees whose limbs were crushed by “the Beast” when they fell from the train. Yet for many the risks of “the Beast” were preferable to alternative routes, where they believed they would encounter more official corruption and criminal groups.[10]Amputees at the Albergue Jesus El Buen Pastor in Tapachula, Chiapas, a shelter for injured migrants, have fashioned wheelchairs out of plastic chairs.[11] One man, a double amputee, realized the irony behind his higher quality wheelchair. He told me that in 2006, Maria Shriver, who was married to Arnold Schwarzenegger, the governor of California at the time, came briefly to the shelter to donate fifteen wheelchairs. He told me “It was nice of her to donate the chairs,” but he disliked Schwarzenegger’s politics, especially concerning immigration.[12] “No he didn’t come,” he said. “We wouldn’t accept him if he did.”

Image 3: Photo of a make-shift wheelchair at Albergue Jesus El Buen Pastor in Tapachula, Chiapas – Photo Credit: Rebecca B. Galemba

The lesson from the U.S.-Mexico border is that the militarization of enforcement does not stop unauthorized border flows (Andreas 2000). When security escalates, smugglers become more sophisticated, violent, and demand higher fees, migrants pursue more dangerous routes, and officials increase bribes (ibid.). In turn, the border policing apparatus expands to combat it in a spiral of mutual escalation (ibid.). In 2012, the U.S. budget for immigration enforcement was $18 billion, larger than all other federal law enforcement agencies combined, despite evidence that such escalation may be counterproductive (Preston 2013). A similar border security approach is exported to Mexico, without enough consideration of judicial and policing reform, corruption, causes of migration, and a lack of transparency and accountability in policing institutions (Isacson et al. 2014). In this context, further feeding the current security and migration infrastructure has led to an escalation in human rights abuses. For example, human rights activists point to concerning implications for migrant rights as Grupo Beta, whose purpose is to aid migrants, has now been enlisted to help Mexican authorities conduct migrant raids (Stanton 2014).

In 2014, The Merida Initiative,[13]a security agreement established between the U.S. and Mexico in 2008 to combat drug trafficking and transnational crime, directed increased funds and attention to “creating a 21st century border” and securing Mexico’s borders (Isacson et al.: 24). As of February 2014, The Mérida Initiative allocated $112 million in technology for border security including training, inspection equipment, and infrastructure, including additional small amounts for Navy/Marine training and facilities from the Defense Department’s counter-narcotics budget (ibid.). Most of this funding has gone to the northern border, but the southern border is now also becoming a priority (ibid.). Yet militarizing security forces in Mexico and Guatemala through U.S.-backed initiatives like Merida and Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI[14]) has not only failed to stem the drug war, but Mexico’s war on the cartels has also left 80,000 dead, 27,000 disappeared, and thousands displaced and since 2006 (MAWG 2013: 3; Abrego 2014). Such approaches are worrisome in regions where the military continues to be associated with human rights abuses and impunity. The United States cut off funding to Guatemala’s military in 1990 due to human rights abuses. Despite this, conditions have loosened and these restrictions do not apply to Defense Department funds, from which $27.5 million was given to Guatemalan security forces for counter-narcotics control form 2008-2012 (Isacson et al. 2014: 29; MAWG 2013). As David Bacon (2014) warns, “giving millions of dollars to some of the most violent and rightwing militaries in the Western hemisphere…is a step back towards the military intervention policy that set the wave of migration into motion to begin with.”

Mexico’s current approaches to tackling border issues, such as the Southern Border Program, do not contain sufficient measures to protect migrants or prosecute corrupt officials. While the program stresses migrant protection as a key component, Jorge Urbano, Director of the Program on Migration at the Iberoamerica University, expressed doubts that “if there is no qualified human capital…professionally trained to do a job that requires expertise in the subject of human rights, the measure…will result in little more than merely good intentions” (Langner 2014, translation mine). The program also does not address the concerns of migrants in transit (Langner 2014).[15] Rubén Figueroa, Coordinator of the Mesoamerican Migrant Movement in the Southern Region, asserts that:

the federal government has applied the Southern Border Plan as a police action to detain and deport the largest number of migrants…within this plan there are no provisions to prevent crimes…In the last decade more than 70,000 migrants have disappeared in Mexico and there are no mechanisms to denounce these disappearances when family members are in Central America[16] (Blanco 2014, translation mine).

Tasking Mexico’s migration institutions and enforcement agents with bolstering border security, regularizing migration, and protecting migrant rights raises additional concerns as critics doubt the ability of Mexico’s National Institute of Migration (INM) to implement immigration laws and respect human rights. In 2013, the INM ranked 8th in the number of human rights abuses reported to Mexico’s National Human Rights Ombudsman (Isacson et al.: 32). The federal police and military ranked even higher in terms of abuses. According to Casa del Migrante in Saltillo in 2013, the federal police received the most denunciations for migrant abuses, even ahead of the Zetas cartel and maras gangs (Ureste 2014a). It is evident that strengthening security does little to make people feel secure. One merchant complained to Mexican journalist Manu Ureste, “as there are more checkpoints, there is more corruption” (Ureste 2014b, translation mine). As soldier demanded money to look through her bags, the merchant laughed when asked if the additional checkpoints made people feel more secure (ibid.). Instead, she saw the checkpoints as an opportunity for officials to distribute money amongst themselves (ibid).

To further understand Mexico’s approach to Central American migrants, it is important to note that Mexico accepts very few refugees–last year only 208 Central Americans (Kahn 2014). Many migrants are deported before they can pursue claims or they are detained indefinitely in INM’s poor facilities while filing (Isacson et al. 2014: 33). Once detained, migrants have a miniscule chance of advocating for an asylum case (IAHCR 2013). At one Mexican detention facility I visited in 2007, the women told me the men were denied water. Visits with their husbands in a different cell depended on the discretion of individual agents. One woman said the only reason the immigration delegate in charge came to check on them that day was because I was present. “Normally,” she said, “they yell at us and insult us.” Most detainees did not know how long they would remain in INM facilities or when they would be sent home. Mexico has recently made some efforts to decriminalize migration in 2008, as well as to enable migrants to seek justice for abuses regardless of status under the General Population Act in 2010 (IAHCR 2013). Nonetheless, detention remains the norm and protections have been insufficient to stem abuses. A recent Washington Office on Latin America report cautions:

Given the widespread and well-documented involvement of Mexican authorities with human smugglers and organized crime, increased immigration enforcement in Mexico is likely to accomplish little, and will only contribute to the further enrichment of corrupt officials and criminals, and to the victimization of innocent migrants (Meyer and Boggs 2014).

We need to become attuned to the reasons why people migrate and why they go where they do; this forces us to look in the mirror at foreign intervention, devastating trade policies, and inconsistent and insufficient immigration and refugee policies.[17] Pushing the crisis elsewhere through increasingly militarized means not only does not work, but it also leaves death and violence in its wake. Moreover, just as the crisis imagery obscures the fact that such problems have long been in the making, it also makes the issues seem to disappear once media and policy attention dissipate. Instead, Joseph Nevins (2002: 171) points to how the political-economic context and political elites shape our perceptions of crisis even when actual conditions may remain similar.

The power of the U.S. to control the border has become a normalized response to larger economic, political, and global anxieties (Nevins (2002: 37). Laying bare the social, historical, and political processes by which border policing has become a normalized mode of nation-building can help us question the implications of extending such exercises of power beyond and within national borders (Nevins 2002; Nevins 2014). As witnessed by the suspicions of illegality surrounding the Mexican bus’ journey, the U.S. has extended its border surveillance practices to Mexico, effectively undermining its sovereignty. Mexico and the U.S. have also instituted internal borders like the checkpoints depicted along the bus trip while the U.S. has implemented various practices of governance (e.g. E-Verify, Secure Communities, workplace policing, and the denial of driver’s licenses in various states) that increasingly delimit and criminalize the movement and existence of immigrants, creating what Nuñez and Heyman (2007) term, “entrapment processes” (also see Nevins 2014).

The restriction of rights based on national borders, coupled with the presumption that border policing can effectively guarantee these rights, relies on an assumption that threats to a nation come from outside of its borders and that such threats should therefore be combatted at the border. The normalization of this logic has made the granting and withholding of basic rights conditioned on national borders appear beyond reproach.[18] Such national frames of concern further contribute to the exploitation and abuse of migrants in transit as well as in the U.S., as their rights are either outright devalued or all too easily suspended in the name of security.

Image 4: Mural of the difficult northward journey, which depicts an imposing border with a narrow entryway between the United States and Mexico at the Casa del Migrante in Tecún Umán, Guatemala. - Photo Credit: Rebecca B. Galemba

Footnotes

- http://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/Mexico_Southern_Border_Strategy.pdf - The program intends to regularize border movements, simplify and extend regional visitor and worker permissions, improve infrastructure and border security, protect migrants, coordinate with Central American governments to enhance border cooperation and combat criminal groups, and to improve interagency collaboration within Mexico (Wilson and Valenzuela (2014: 1-2).

- Also see Nevins (2002) for similar justifications for the U.S.-Mexico border buildup. I would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for noting the parallels with Nevins’ work.

- See work by Andreas (2000), Nevins (2002), and Dunn (1996) for example.

- For example, Rosalva Aída Hérnandez-Castillo (2001) details how the Mexico-Guatemala border played a strong role in the establishment of the Mexican state as Mexican officials in the early 20th century forced indigenous Mexican border residents to assimilate, burn their traditional clothing, and abandon indigenous languages that shared close cultural affinities with neighboring Guatemala.

- http://www.worldpress.org/0901feature22.htm

- Mexico’s implementation Plan Sur was largely motivated by the expectation that the U.S. would improve the treatment of Mexican migrants if Mexico strengthened its own southern border enforcement. However, such an agreement, debated just a few days prior to September 11, 2001, was abandoned after the terrorist attacks. Plan Sur was implemented and the U.S. regained supremacy over the border agenda (Pickard 2005).

- As described in the first paragraph, identifying Mexicans and Guatemalans at the border is often not a straightforward process due to histories of cross-border marriage, as well as Guatemalan refugee flight and return movements in the 1980s and 1990s.

- http://www.inm.gob.mx/index.php/page/Grupo_Beta - In southern Mexico, however, Grupo Beta has also been implicated in corruption as well as in protection.

- He was referring to the Mara Salvatrucha, or MS 13, gang. See http://www.insightcrime.org/el-salvador-organized-crime-news/mara-salvatrucha-ms-13-profile. Another gang that preys on migrants is Barrio 18. See http://www.insightcrime.org/honduras-organized-crime-news/barrio-18-honduras

- Despite this man’s perception, migrants riding the train do also encounter abuses by officials and criminal groups. See Nazario (2014) for evidence of such abuses.

- http://www.alberguebuenpastor.org.mx/index.php/en/the-shelter

- Arnold Schwarzenegger was well known for his anti-immigration politics in California, especially his support for Proposition 187, which would have denied basic services like health and education to undocumented immigrations. After re-election in 2006, he apologized for some of his anti-immigration stances. http://www.ontheissues.org/celeb/Arnold_Schwarzenegger_Immigration.htm

- http://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R41349.pdf

- http://www.state.gov/p/wha/rt/carsi/

- The program focuses more on Guatemala and Belize (for example in terms of extending regional visitor cards) rather than extending the frame of concern to increasing migrant movements from Honduras and El Salvador.

- The Mexican government does not have a database to enable it to search for missing Central Americans (Blanco 2014).

- David Bacon (2014) provides a succinct and convincing directive while debunking common immigration myths.

- See Linda Bosniak (1995) of the implications of only considering claims for justice within national terms.

Works Cited

Abrego, Leisy J. July 9, 2014. Rejecting Obama’s Deportation and Drug War Surge on Central American Kids. The Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/leisy-j-abrego/rejecting-obamas-deportat_b_5568358.html Accessed December 11, 2014.

Andreas, Peter. 2000. Border Games: Policing the US-Mexico Divide. Cornell University Press.

Archibold, Randal C. July 19, 2014. On Southern Border, Mexico Faces Crisis of Its Own. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/20/world/americas/on-southern-border-mexico-faces-crisis-of-its-own.html Accessed December 11, 2014.

Bacon, David. July 8, 2014. Debunking 8 Myths About Why Central American Children are Migrating. In These Times with Liberty and Justice For All. http://inthesetimes.com/article/16919/8_reasons_u.s._trade_and_immigration_policies_have_caused_migration_from_ce Accessed December 11, 2014.

Benítez Manaut, Raúl. 2003. La Seguridad Internacional, la Nueva Geopólitica Continental y México. In Francisco Rojas Aravena, ed. La Seguridad en América Latina pos 11 de Septiembre. Caracas, Venezuela: Nueva Sociedad, FLACSO-Chile. Woodrow Wilson Center, Paz y Seguridad en las Américas. Pp. 75-100.

Birson, Kurt. September 23, 2010. Mexico: Abuses Against U.S. Bound Migrant Workers. NACLA. https://nacla.org/news/mexico-abuses-against-us-bound-migrant-workers Accessed December 11, 2014.

Blanco, Manuel. 7 de Diciembre, 2014. Políticas migratorias, “pura pantalla” Péndulo de Chiapas. http://www.pendulodechiapas.com.mx/municpios/58-de-chiapas/34717-politicas-migratorias-pura-pantalla Accessed December 11, 2014.

Bosniak, Linda S. 1995. Opposing prop. 187: Undocumented immigrants and the national imagination. Conn. L. Rev. 28: 555.

Cruz Burguete, Jose Luis. 1998. Identidades en Fronteras , Fronteras en Identidades: Elogio a la Intensidad de los Tiempos en los Pueblos de the Frontera Sur. El Colegio de Mexico, D.F.

Dunn, Timothy. The Militarization of the U.S.-Mexico Border 1978-1992: Low-Intensity Conflict Doctrine Comes Home. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Hernández Castillo, R. Aida. 2001. Histories and Stories from Chiapas: Border Identities in Southern Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IAHCR). December 30, 2013. Human Rights of Migrants and Other Persons in the Context of Human Mobility in Mexico. Organization of American States. http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/migrants/docs/pdf/Report-Migrants-Mexico-2013.pdf Accessed December 11, 2014.

Isacson, Adam, Maureen Meyer, and Gabriela Morales. August 2014. Mexico’s Other Border: Security, Migration, and Humanitarian Crisis at the Line with Central America. Washington Office on Latin America. Pp. 2-44.

Kahn, Carrie. August 1, 2014. As Flow of Migrants Into Mexico Grows, So Do Claims of Abuse. New England Public Radio. http://nepr.net/news/2014/08/01/as-flow-of-migrants-into-mexico-grows-so-do-claims-of-abuse/ Accessed December 11, 2014.

Langner, Ana. July 8, 2014. Programa Frontera Sur, hecho al vapor. El Economista. http://eleconomista.com.mx/sociedad/2014/07/08/programa-frontera-sur-hecho-vapor Accessed December 11, 2014.

The Mesoamerican Working Group (MAWG). November, 2012. Rethinking the Drug War in Central America and Mexico. http://www.ghrc-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Mesoamerica-Working-Group_Rethinking-Drug-War-Web-Version.pdf Accessed December 11, 2014.

Meyer, Maureen and Clay Boggs. June 27, 2014. The Other Crisis: Abuses Against Children and Other Migrants Traveling through Mexico. The Washington Office on Latin America. http://www.wola.org/commentary/the_other_crisis. Accessed December 11, 2014.

Nazario, Sonia. 2014. Enrique’s Journey. New York: Random House.

Nevins, Joseph. 2002. Operation Gatekeeper: The Rise of the “Illegal Alien” and the Making of the U.S.-Mexico Boundary. Routledge: New York and London.

Nevins, Joseph. 2014. Policing the Workplace and Rebuilding the State in “America’s Finest City”: US Immigration Control in the San Diego, California-Mexico Borderlands. Global Society 28(4): 462-482.

Núñez, Guillermina Gina, and Josiah McC Heyman. 2007. Entrapment processes and immigrant communities in a time of heightened border vigilance.” Human Organization 66(4):354-365.

Pickard, Miguel. 2005. Trinational Elites Map North American Future in ‘NAFTA Plus.” Americas Program. http://www.cipamericas.org/archives/1357

Preston, Julia. January 7, 2013. Huge Amounts Spent on Immigration, Study Finds. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/08/us/huge-amounts-spent-on-immigration-study-finds.html Accessed December 11, 2014.

Sánchez, Gabriella. July 30, 2014. Contextualizing the Discourse of Unaccompanied Minors. Anthropology News. http://www.anthropology-news.org/index.php/2014/06/30/contextualizing-the-discourse-of-unaccompanied-minors/ Accessed December 11, 2014.

Stanton, John. December 7, 2014. The Immigrant Crackdown. Mexico Has Brutally Choked Off the Flow of Undocumented Immigrants into the U.S. BuzzFeed News. http://www.buzzfeed.com/johnstanton/mexico-has-brutally-choked-off-the-flow-of-undocumented-immi Accessed December 11, 2014.

Ureste, Manu. 30 de Enero, 2014a. Federales extorsionan a más migrantes que el crimen organizado. Animal Politico. http://www.animalpolitico.com/2014/01/federales-con-mas-denuncias-de-extorsion-migrantes-que-el-crimen-organizado/#axzz37Br0GA9m Accessed December 11, 2014.

Ureste, Manu. 15 de Diciembre 2014b. Especial: De Tonalá a Tapachula, 224 kilómetros de retenes y corrupción. Animal Político. http://www.animalpolitico.com/2014/12/especial-de-tonala-tapachula-224-kilometros-de-retenes-y-corrupcion/ Accessed December 15, 2014.

Vila, Pablo 1999. Constructing social identities in transnational contexts: the case of the Mexico-US border. International Social Science Journal 51(159): 75-87.

Wilson, Christopher and Pedro Valenzuela. July 11, 2014. Mexico’s Southern Border Strategy: Programa Frontera Sur. Wilson Center: Mexico Institute. Pp. 1-3. http://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/Mexico_Southern_Border_Strategy.pdf Accessed December 11, 2014.