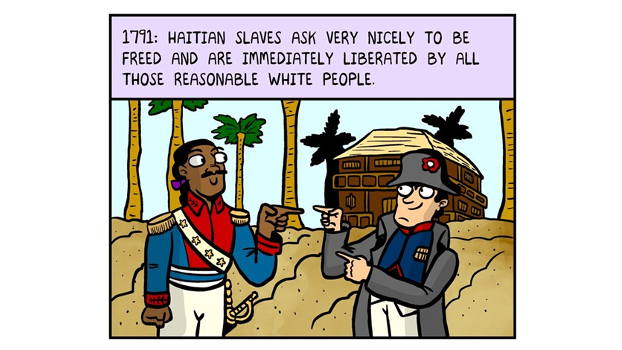

A cartoon joking about the ease with which Haitians gained their freedom from French rule bounced around Facebook this week, as protests continued in Baltimore following the death of Freddie Grey while in police custody. For those of us who study the Haitian Revolution, it evoked a sad chuckle and a knowing smile. We laughed sadly because we know that the idea that Haitians easily gained their freedom is preposterous, and we smiled knowingly because we recognize how relevant the joke is to today’s protests in Ferguson, New York, and Baltimore. For those of you who think the comparison of Baltimore in 2015 to Port-au-Prince in 1791 is going too far, let me explain the joke.

By the end of the 18th century, the French were proud to own the richest colony in the world, Saint-Domingue, where tens of thousands of enslaved Africans were disembarked off ships every year, most of them with a life expectancy of less than five years. The enslaved revolted in 1791, gained their freedom in 1793, and eventually declared national independence in 1804 after the French sent an expedition to re-establish slavery. Haiti was born.

In 1804, it was shocking that a group of formerly enslaved Africans and their descendants dared to form their own nation founded on the abolition of slavery. By this time, to be enslaved was a social status associated with people of African descent in the Americas, so fighting slavery required fighting the racism intrinsic to the institution. Haiti’s existence challenged the narrative that the West told itself: certain people were meant for enslavement and exploitation; therefore, the system of inequality foundational to the Americas was simply normal, not unjust. The West, faced with the shock of Haiti’s existence, worked hard to keep that narrative alive.

In order to promote that story, Haiti was maligned. Haitians were considered violent, barbaric, and incapable of running a nation. Actions such as Haiti’s 1825 agreement to pay France billions of dollars in exchange for recognition, which weakened the Haitian economy from the start, were used to prove that Haiti couldn’t stand—not to show that the West in fact needed it to fail. This attitude, this desire to prove true the “doomed to fail” narrative, is alive and well two centuries later and it’s closely related to the story that we tell about protests in Ferguson, New York, and Baltimore.

In 2010, the day after an earthquake in Haiti killed over three hundred thousand people, Pat Robertson announced that Haitians were paying for their “pact with the devil.” What was this “pact” exactly? Robertson suggested that in order to gain their freedom, Haitians needed the help of an evil force, to which they still owed their independence today.

Let’s break down this absurd accusation—Haitians’ ancestors dared to assert that they were not property; they dared to assert that their lives mattered. What made their freedom and eventual national independence possible? Their determination? Their inner sense of humanity? Their dream of a better life? No, says Robertson, opposing the institution of slavery was the “devil’s” work. And what’s worse, Robertson suggests that hundreds of thousands of people deserved to die two hundred years later because of it. Yet the most detrimental part of this accusation is that it props up the idea that violence belongs to and embodies Haiti and Haitians—not to the institution of slavery that offered misery and death to some and wealth and prosperity to others.

The fact that, two centuries after the first successful slave revolt in the Americas, people continue to locate violence only in the opposition to oppression rather than in the system that oppresses brings us to Ferguson, New York, and Baltimore today. Those who fight back and oppose a system that perpetuates inequity are “thugs” much like Haitian revolutionaries were “brigands.” We overlook the fact that life expectancy varies dramatically by neighborhood in Baltimore, the fact that minor traffic violations can ruin the lives of those who can’t afford to pay the fines associated with tickets, or the fact that certain police departments find racism funny. Slavery was abolished in the United States a century and a half ago, over six decades after Haitians claimed their freedom. Economic disparity and racism, both intrinsic to this institution that was foundational to the beginning of the Americas, have not been fully abolished. This, sadly, is why 2015 bears a striking resemblance to 1791.

Now you get the joke. Funny, huh?